A Simple, Time-indexed, NAND Flash-aware Filesystem for CubeSats

Introduction

This summer I worked on a custom QSPI NAND flash driver and filesystem for an in-house PCB at UCLA’s Electron Loss Field Investigations Lab (ELFIN). This was mainly to support the persistent storage of data products from another custom board as well as housekeeping data from the main board.

In what I saw online, most developers tended to use someone else’s FTL (flash translation layer) with built-in wear leveling and page allocation for arbitrary reads and writes to flash. I was considering using dhara, but I ended up not doing this.

While dhara and other FTL’s, or even filesystems like littlefs are lightweight compared to Linux filesystems like Ext4 or Windows, for our custom PCB, they still imposed too much overhead, especially with our anticipated data rates. In addition to making our single-threaded microcontroller slower, overhead increases the board’s power consumption: a dire issue when on most space flights, the entire payload will be deeply power-constrained. It was instead more effective to implement a custom solution that stayed as close to NAND flash operations as possible.

The board I was working on is known as SDPI (Software-Defined Payload Interface), which is UCLA’s winning submission to the NASA Techleap Universal Payload Interface Challenge. SDPI would fly on the ELVES weather balloon mission in New Mexico, which meant that the team had a hard deadline of September 2 to build and validate a working system, from data collection on board to analysis on the ground.

My task was to write a driver to interface with our four on-board NAND flash chips using QSPI and implement filesystems on top of the four flash chips to support storing, searching, and reading data packets from SDPI itself and from another board (FGM20) that would be connected to SDPI. The external flash (so-called because our microcontroller also had its own internal flash) would additionally store scripts and a superblock region.

To support the filesystem on the ground side, I wrote endpoints and designed a transmission sequence to transfer data from filesystems back to a ground server, which stores it in a PostgreSQL database. The end goal was to verify the entire data pipeline, of data from another board to SDPI, into SDPI’s flash via the filesystem, and into the ground server database by a read request.

External NAND Flash

The beauty of using NAND flash is that it is highly cost-effective and space-efficient, but it poses some weird design challenges that make it tricky to implement arbitrary writes and erases.

The filesystem was built on four Alliance Memory SPI NAND flash chips, each with ~ 1 GB of memory. The filesystem is currently designed so that two chips are held in reserve (unused). In the future, I plan to use those chips to mirror all writes to the main two flash chips for redundancy and corruption check purposes.

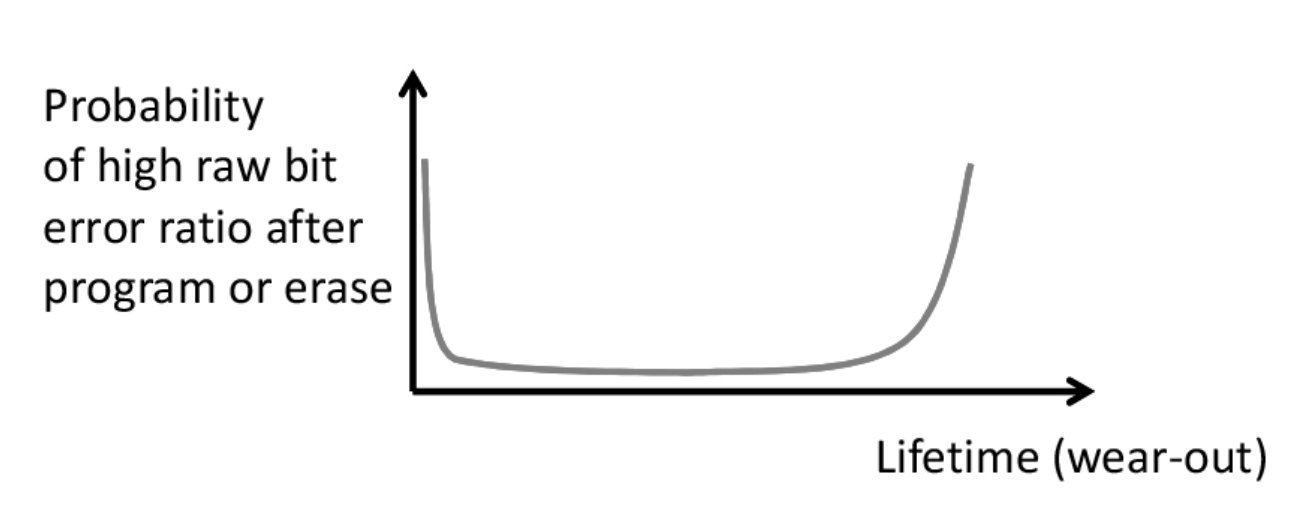

From the datasheet, each flash chip has 4096 blocks, each block has 64 pages, and each page has 4352 bytes… Except this is not strictly true. Each chip has around 9 or 10 blocks at the end marked as bad blocks, that were unable to be programmed upon manufacture. Over time, flash chips also accumulate bad blocks as a result of approaching the erase/program cycle limit.

Additionally, 4352 bytes is not evenly divisible by two, making full, continuous addressing of all the bytes difficult. The datasheet internally addresses with rows and columns, where row addresses select blocks and pages, while column addresses select the byte in the page.

In addition to inconvenient addressing, NAND flash’s other key restriction lies with how writes work. Writing data to flash utilizes the “Page Program” operation, which works by programming bits down one page at a time. In other words, if you program a page with arbitrary content buffer1 and then (without erasing) program it again with buffer2, the stored data becomes buffer1 & buffer2 (bitwise AND), not buffer2 alone. Correct page programming therefore requires the page to be in the erased state (programmed up to all 1s) beforehand.

Erases, however, operate at the block granularity and return all 64 pages of bits to 1 (read back as FF FF FF …). This inherent mismatch between page-sized writes and block-sized erases requires the use of large buffers (to save the contents of the other pages in a block) or other flash-aware methods.

Most of these issues will be addressed in the virtual flash driver.

QSPI Pin Initialization

Since our microcontroller has four flash chips, there needs to be a way to select which flash chip the SDPI is talking to and reading data from at a given time. This is done with chip select pins, which SDPI needed four of in order to talk to four flash chips. The particular microcontroller normally only gives one pin for use with the QSPI bus (to control one flash chip peripheral), so the electrical engineering lead that designed the board used three other normal GPIO (general purpose input output) pins on our microcontroller as the chip select pins for the remaining flash chips.

On the board, there are four data lines for QSPI NAND Flash (FLASH_QIO0, FLASH_CLK, FLASH_QIO2, FLASH_QIO3) that were set to a certain peripheral mode and all routed to all four flash chips. Each flash chip also has the aforementioned GPIO chip select pin to toggle whether the chip was in use. On every flash operation, the QSPI NAND Flash driver is toggling only one flash chip to use, pulling the chip select pin down to enable and up to disable use of the flash chip.

This was a major source of confusion for me in the beginning of this project, because I was not sure in what mode these pins should be initialized, and what this meant from a functional perspective. Later on, with the help of my project manager and some datasheet reading, I realized how it worked physically, as explained above.

QSPI NAND Flash operations

The major operations of the NAND flash are: reading a page (“Page Read”) writing a page (“Page Program”) erasing a block (“Block Erase”)

These are generally implemented as a call to the transfer function, which takes a struct bundling a few parameters:

typedef struct {

qspi_flash_chip flash_chip; // an enum for which of the 4 flash chips you are using

uint8_t flash_opcode; // Command/instruction byte

uint32_t address; // Address (up to 24-bit)

uint8_t address_size; // Address size in bytes (0-3)

uint8_t *data;

size_t data_size;

bool write_operation; // true for write, false for read and commands

} qspi_transfer_t;

The transfer function sends the command opcode and corresponding arguments byte by byte across the SI pin of the QSPI connection to the respective flash chip. Beyond the three core functionalities listed above, there are numerous helper functions that also use this transfer function.

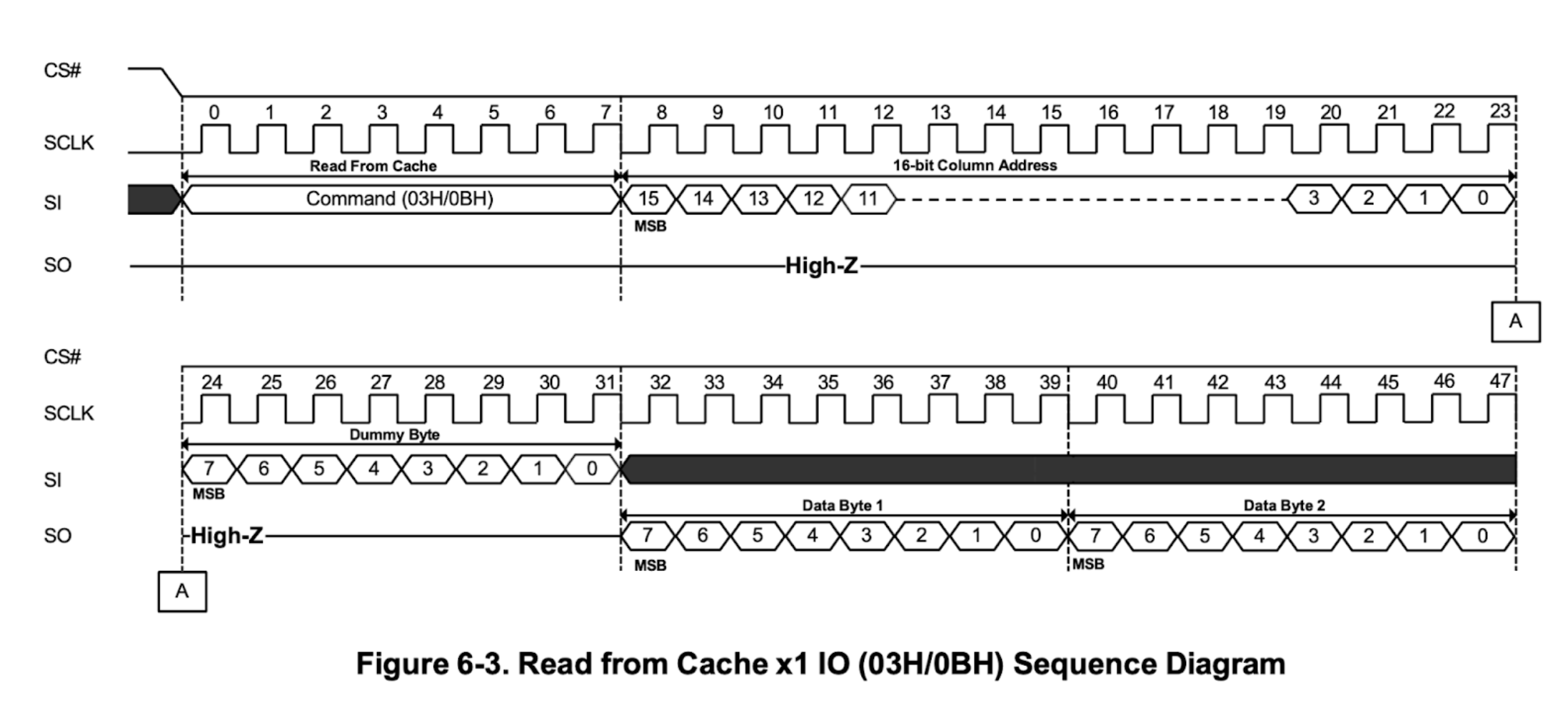

To understand some common NAND functions, let’s consider “Page Read”. First this calls the NAND flash “Read to Cache” command to load the respective page into cache. The flash driver waits on this command’s completion by polling the byte in the status register. Once this command finishes, the driver calls a “Read from Cache” command to load the contents of the page-sized cache into the buffer that was passed to the NAND flash function.

A “Read from Cache” command to the NAND flash looks like this from the datasheet.

The NAND flash chip exposes a page-size “cache” (4352 bytes) that is the entrypoint of all data flash operations. This limits reads to a page at a time and similarly limits writes to a page at a time. Any operations larger than a page must be abstracted above and handled with additional logic. Both the read and the write operations consist of multiple NAND Flash commands.

The complete read process thus looks like the following:

- Read from NAND flash array into cache (“Page Read to Cache”). Poll status until command is complete.

- Read from the cache into the buffer (“Page Read from Cache”) to pass back to the calling function.

The write (page program) process looks like the following:

- Load contents to be written from a buffer into the cache (“Program Load”).

- Write contents of cache to flash array (“Program Execute”).

- Poll status for completion and errors (“Get Feature”).

In general, the more costly NAND flash operations require a few cycles of polling status to ensure completion of the operation before proceeding with the function. Notably, block erase takes around five cycles of polling status, more than all other operations.

Creating the “Virtual Flash” driver

Virtual flash is an abstraction on top of the QSPI NAND flash, simplifying the address across all 4 flash chips into two banks of addresses with linear, contiguous addressing and clean functions for other components of the whole SDPI codebase to use.

The important functionalities in the virtual flash driver were the following:

- arbitrary reads

- arbitrary writes (known as

erase_write) - writing a page

To support these functionalities, a function to translate between physical flash addresses with a 24-bit row and 16-bit column addresses per flash chip to a single 32-bit virtual flash address. While the NAND flash uses 13 bits to address all the bytes in a page, the NAND flash page size is only 4352 bytes. This meant that the addressing was not continuous (2^13 is 8192; if you keep counting from the end of a page size at 4352, you would run into space that does not correspond to anywhere actually on the flash).

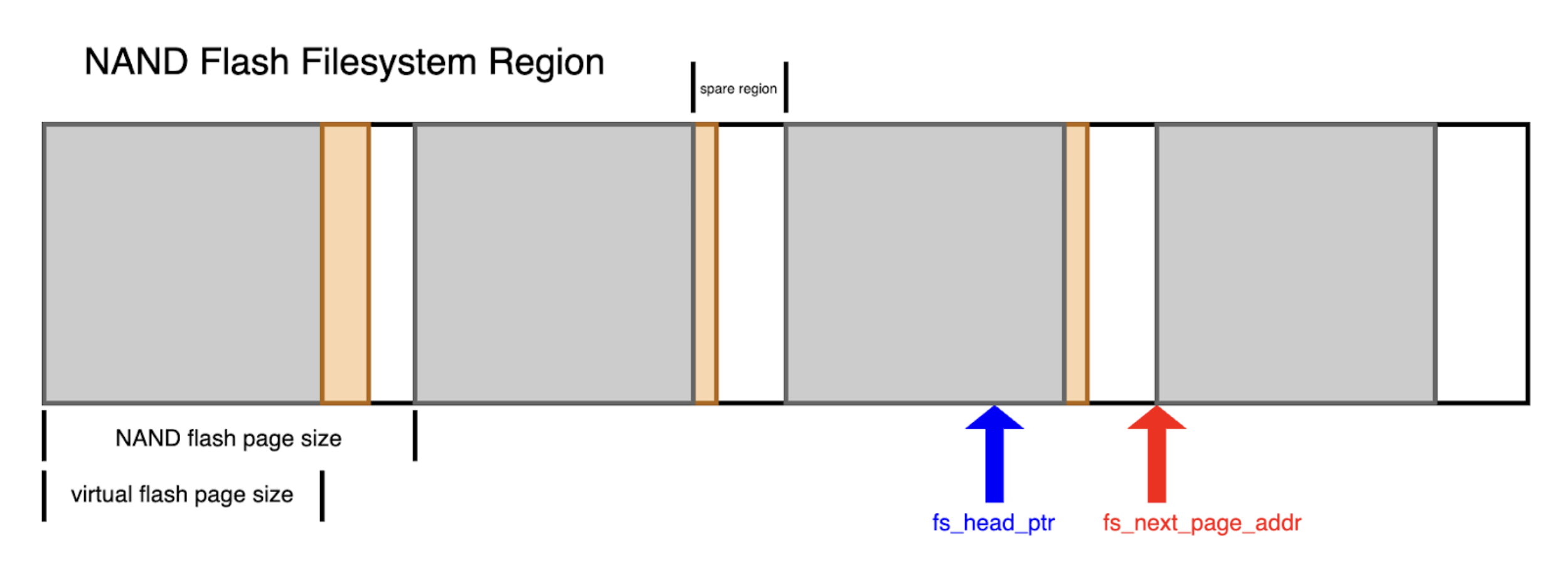

This is annoying for a clean and continuous address space, so I cut each page size down to 4096 (2^12) to get rid of this issue. Incrementing by hex 0x1000 gets you to the next page, and incrementing by hex 0x40000 gets you to the next block, though future developers shouldn’t have to think about block boundaries except in operations concerning erasing. In flash terminology, the extra space is typically known as the spare region, and it turns out having spare regions is not uncommon in NAND flash.

Pages sizes of 4096 bytes are easy to operate on by virtue of being a power of 2. Instead of dividing or doing modulo on awkward sizes of 4352 to translate from virtual address to flash row and column addresses, bitmasks could now be used. Division and modulo operations take significantly more clock cycles than bitmasking, which was an important consideration considering how often addresses would be translated in normal flash operation.

From this design, SDPI loses around 5.9% of our storage capacity, which for flash chips of 4 GB total capacity on an embedded device, felt like an acceptable loss, especially since SDPI would lose more when mirroring is implemented. Having the extra 256 bytes of space is not a bad thing. Early in the design process, my project manager suggested adding page metadata (such as when a packet ends in the page) or error correction bytes (fairly common practice). While I did not yet implement this, I discovered the extra space is useful for an operation called filesystem recovery, which will be described later.

Another important aspect of the virtual flash driver was the function erase_write, intended to allow for arbitrary writes. Because of the peculiarities of NAND flash, arbitrary writes are complex and inefficient, but it was still important to expose a function to do this in order to support other functionalities of SDPI that used the external flash.

Each call to erase_write does the following:

- “Page Read” every page in the block you’re going to write to, save contents to a block-sized buffer called

block_copy. - Edit

block_copyto add the requested edits (as specified by the virtual flash address and write buffer given toerase_write). - Block erase the block that contains the location of the writes on the flash chip.

- Check status, exit if fail.

- For all the pages in the block, “Page Program” every page with that page’s worth of content from

block_copy.

This function is used for rare operations, such as writing a new script to flash, because of its overhead.

Packet Filesystem(s)

The key issue of filesystem design was that SDPI receives data from other boards and itself (housekeeping packets) that are of varying sizes, none of which divide evenly into a page size. For example, SDPI housekeeping packets are 55 bytes, while most data packets from the FGM20 board are 19 bytes long. The naive solution would be to call the erase_write function every time the filesystem receives a packet. However, this approach would be highly inefficient, as it would require erasing and rewriting an entire block—278,528 bytes (4352 bytes × 64 pages)—for each incoming packet of only ~20 bytes. This would result in extreme write amplification, wasted bandwidth, and unnecessary wear on the flash memory.

These packets should be stored in the flash filesystem as fast as possible (with as little overhead as possible) because of our fast sample rates on our instruments (up to 128 sps for one kind of measurement, and 8 total types of data/housekeeping packets) which results in around 7 KB per s of data collection thrown at our single-threaded microcontroller. While the microcontroller is storing data in flash, it also should be able to respond to query and read requests, and other commands sent from a ground server in standard operation.

The filesystem design imposes a few restrictions on where and how the data is stored. Instead of putting all data packets into one big filesystem with varying packet lengths, each packet type is given its own filesystem and defined regions of flash based on its sample rate (samples/packets per second).

The beginning nine bytes of each data packet is the timestamp represented in BCD (binary-coded decimal) format. In this sense, a packet filesystem is organized sequentially by both increasing addresses and monotonically-increasing timestamps. Because every packet in a certain filesystem is the same size and the timestamp of each packet is the same size at the beginning of the packet, searching through a filesystem is simple and fast: increment a packet size, read back and check the timestamp of this packet, and repeat this process.

That is, assuming packets are continuous across pages. Recall that the NAND level page size is 4352 bytes, which is not a clean power of 2. I cut this down to 4096 bytes so that pages are now cleanly addressed by just 12 bits out of the 32 bit virtual flash address. Incrementing to the biggest unsigned number representable by 12 bits carries you over to the next page.

Storing Packets

The main storing functionality of the filesystems is implemented in the function store_packets. The general flow is:

- To first check packet validity.

- Packet size: Is the data passed a multiple of the packet size of this particular packet type?

- Timestamp validity: Is the timestamp of the first packet a valid timestamp? Is the timestamp of the first packet passed in after the timestamp of the last packet this filesystem stored?

- If the data passes the checks, add the data to a page-sized buffer in RAM (allocated at compile time to not take up stack space).

- If the data passed to

store_packetswill overflow that filesystem’s buffer (size of a page), fill the buffer to exactly a page, then write the buffer into the flash region for that filesystem. This will result in at most one incomplete packet at the end of a page. The remaining bytes of that packet will appear in the first bytes of the next page, maintaining a continuous, searchable filesystem. - Update pointers and indexes accordingly.

For each packet filesystem, the following constants are stored to manage it:

- start address

- size of filesystem flash region (in number of blocks)

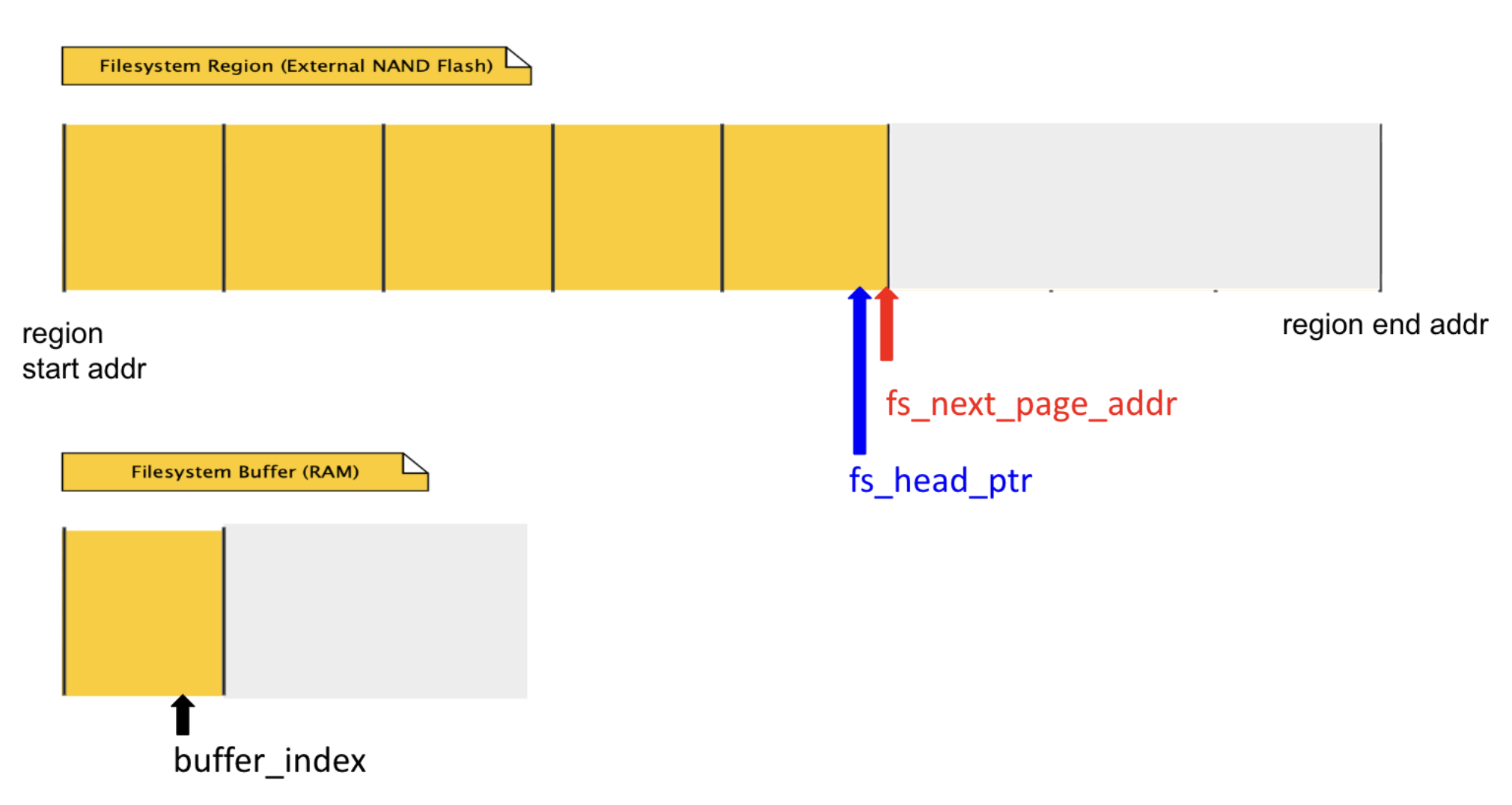

And a few extra special pointers and values that are updated often:

- buffer index: size of content in buffer

- head pointer: start address of the first (and only) incomplete packet, exactly a packet size after the last complete packet

- next page address: the next page to write to in the flash filesystem region

- last packet timestamp: the timestamp of the last packet this filesystem wrote to flash

Of the pointers, the most important are head pointer (fs_head_ptr) and next page address (fs_next_page_addr).

From the perspective of the ground server, fs_head_ptr is the ground truth of how full the filesystem is. It cleanly denotes the end of the last complete packet, and is passed back to the ground server in query and read operations. On the other hand, fs_next_page_addr represents what is actually happening in the filesystem in terms of actual content written to flash, because SDPI writes exactly a page at a time.

The filesystem also needs to support search on timestamps, because ground operations should not be required to keep track of packet addresses in order to downlink packets from SDPI. Due to the design of our filesystem having a continuous address range with packets one after another, the parsing of timestamp data is not too bad. The filesystem simply reads nine bytes for the timestamp at the beginning of the flash region, increments by packet size, reads the next nine bytes, and so on.

While linear search was simple to implement, reliable, and sufficient for this ELVES mission, it will be a problem in the future when data volumes become much larger. Searches for timestamps deep within the filesystem will take significant time, which is a severe penalty when done on a single-threaded microcontroller that currently cannot respond to other commands while reading and downlinking data.

Circular Filesystems

Originally, it was planned for all packet filesystems to be circular. Once the filesystem head pointer and next page address got to the end of the filesystem, SDPI would erase the first block of the filesystem to continue writing more data from there. This feature was removed because it was unnecessary for the ELVES mission given how long our flight was and how full we expected the filesystems to be.

I will still discuss some possible issues and potentially how to address them, but none of the below was implemented on the ELVES mission code.

One such issue is how more blocks need to be progressively erased on the second writing through a particular filesystem. Once a filesystem wraps, the first block is erased, and once that block is filled, the next block should be erased. This means that the file system needs to be aware of block boundaries in NAND flash, in order to keep as much data present in the filesystem for as long as possible.

Once a filesystem wraps, the first block is erased. The filesystem at this time will then see an incomplete packet at the beginning of the first written block in the flash region, breaking queries and reads. The solution is to determine where the first complete packet in that second block (and subsequent blocks) is, whether by modulo or other methods, and define a new parameter to record the current start address of the filesystem. This current start address is also known as the tail pointer, or the last address written to with valid packet data.

Additionally, all filesystem-related operations, including reads, queries, and the underlying search used by queries and reads now need to be aware of proper wrap behavior. From a code organization standpoint, there needs to be a new function called increment_packet_index which properly increments a given packet address to the next packet, wrapping properly by taking into account the actual start and end address of that filesystem flash region.

Communicating with and Downlinking to Ground Servers

To communicate with the ground backend server, I had to design and implement a robust transmission sequence to maintain high data rates with minimum overhead, while still providing error and frame loss detection.

For the sake of clarity, I call the package of data bytes sent together a “frame” to distinguish them from data “packets” that exist in the filesystem, stored from all the instruments connected to SDPI or transmitted to SDPI via other boards. A special kind of “frame” in the filesystem read sequence can contain multiple data “packets”.

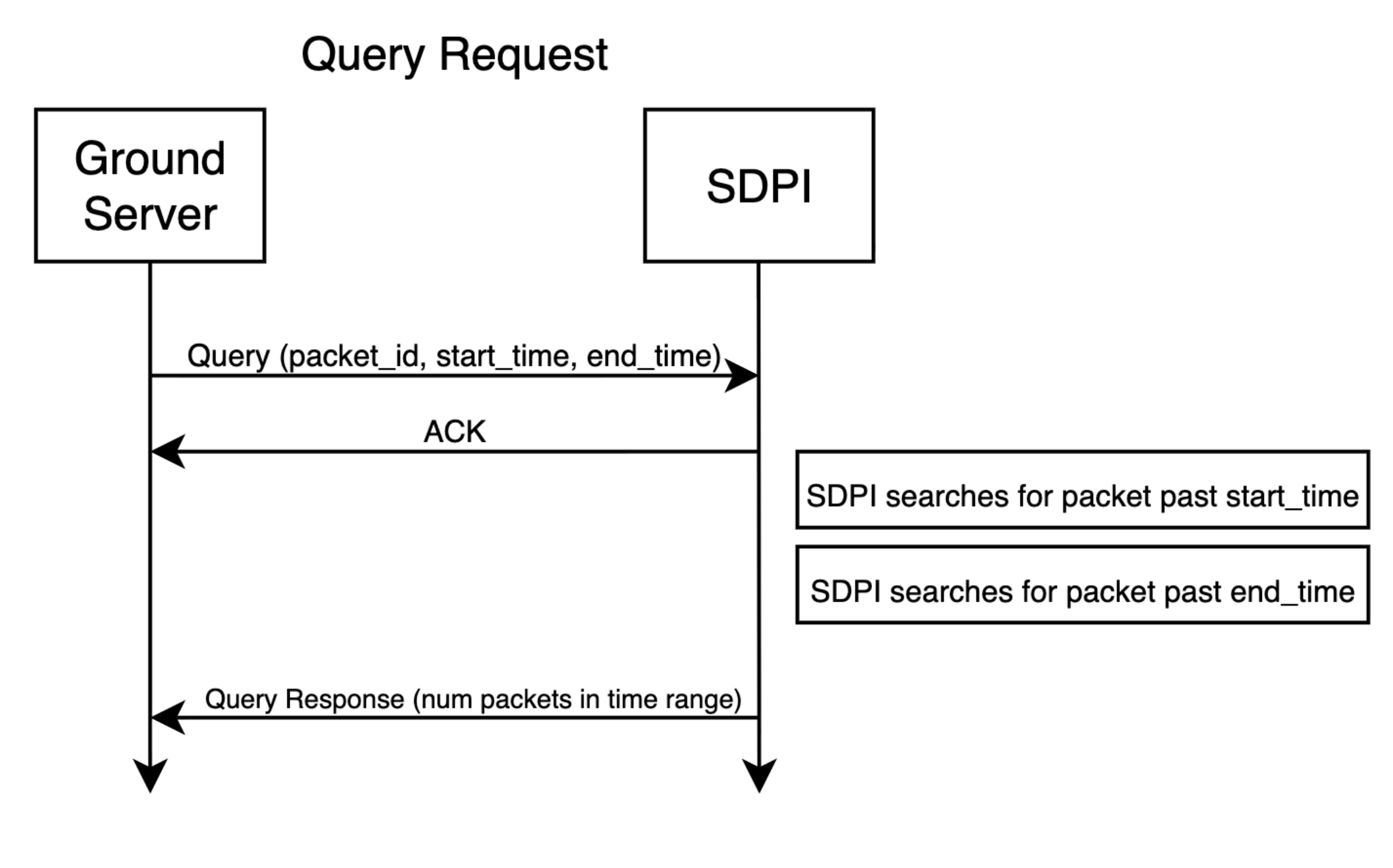

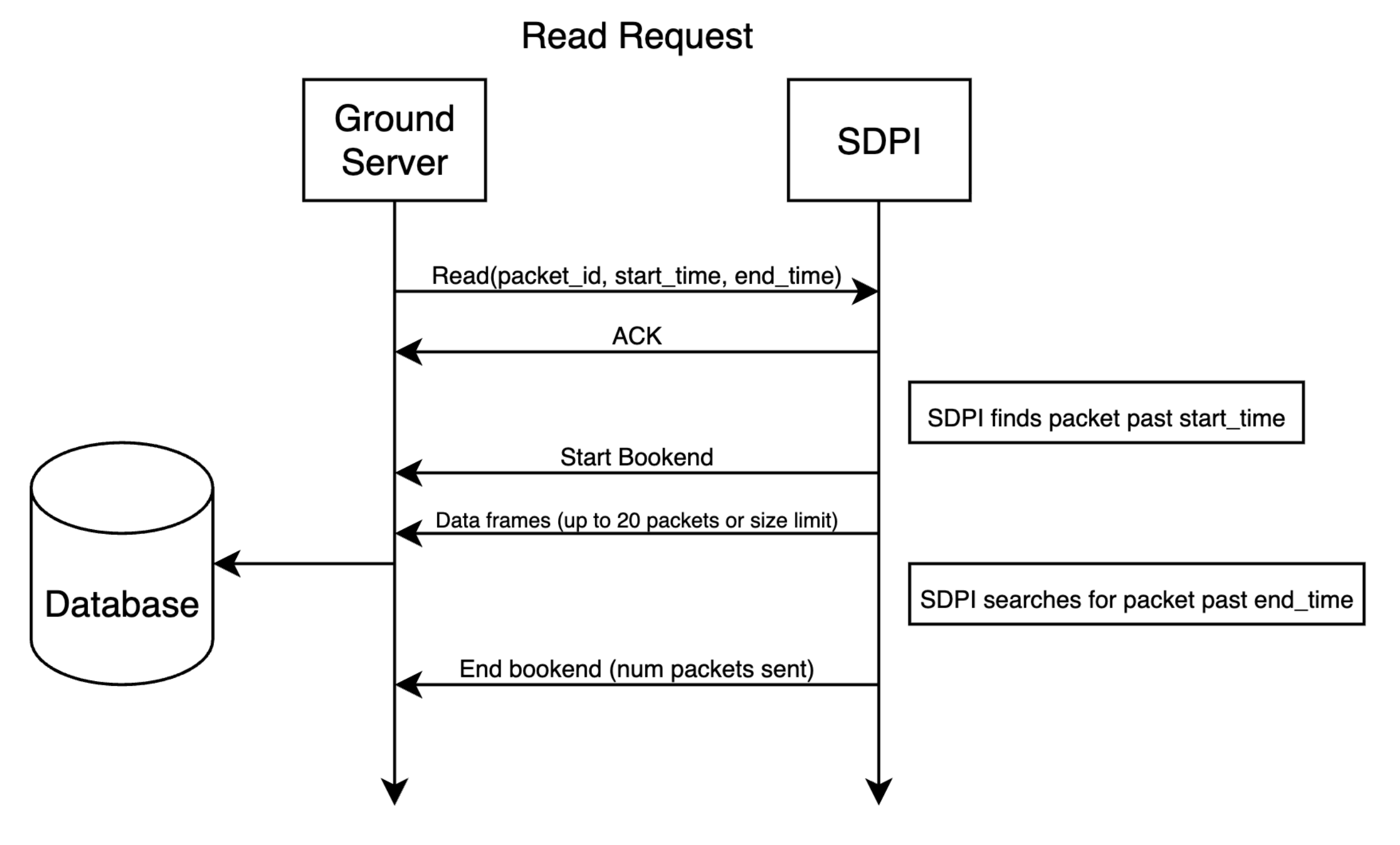

Query and read requests should be sent without the ground having to know at which addresses those packets reside in the filesystem, so they are sent only with the parameters of start and end time, and which filesystem to look in. A query request gives back a count of how many packets are within a time range. A read request gives back both the information of a query request and the actual data packets in that time range. On both operations, SDPI searches through the filesystem of the corresponding data type to find packets from that time range.

A query request looks like the following:

Backend begins by sending a query request to the SDPI board specifying which packet filesystem to look in and for what time range. When SDPI receives a query request, it immediately sends back an acknowledgement frame, essentially echoing the contents of the query it just received. This was done because the search for the first packet past the start_time could take a long time if the packet was very deep in the filesystem. It was determined more effective from the commanding point of view that we got immediate receipts for acknowledgement of query and read requests. After sending the ACK, SDPI searches for the first packet past start_time. If this is found, then it searches for the first packet past end_time, incrementing a count while doing so. Once this process completes, SDPI sends a query response containing the count of packets in this time range, the first packet’s timestamp, the last packet’s timestamp, and the head pointer of this filesystem for bookkeeping on the backend side.

A read request is somewhat similar but has to deal with actually transmitting the data of the filesystems. We cannot send the contents of an entire filesystem (possibly on the order of a hundred megabytes) in one frame and expect the whole transmission to be successful, so we divide the response to a read request into frames. When SDPI is actually in space, we expect to have high frame loss rates. On the ground server side then, we use whatever frames we do receive, along with additional data in special frames called “bookends” to reconstruct a bitmap of the filesystem we were looking at, so we know what packets we lost and what we need to re-downlink.

The start bookend contains the packet ID, filesystem head pointer, and the packet address, and timestamp found by the first linear search by SDPI. The end bookend contains the same information as the start bookend, but also the end packet address and timestamp, as well as the count of the number of packets sent in this read.

The intent of the start and end bookends is to give the backend ground server the information necessary to calculate the number of missing packets in a given timestamp range. This can be done by subtracting the given start address from the end address and dividing by packet size to get the expected number of packets in a timestamp range (technically also an address range). This expected number can then be compared against the actual number of packets received (sum across all frames received) to get a packet drop rate.

Additionally, that the bookends define a start and end of a certain section of a filesystem region in flash, and that the head pointer is returned as well, allows the backend / operators to visualize the state of the filesystem.

Each data frame contains 20 data packets or whatever number of packets fits under roughly a KB (whatever comes first), as well as a packet ID at the beginning of the frame and a numerator (how many packets have been sent so far, including this data frame) at the end. The numerator is essential to the backend ground server because it allows it to order frames if they arrive out of order.

I am grateful that for the ground backend server, I could rely on two of my co-workers to implement the actual details of the processing and data pipeline into the PostgreSQL database. To support their functionality, I added an additional field to my responses for query and reads to identify what kind of frame (acknowledgement, data frame, start or end bookend) a certain frame was. This was because the flight software team had not implemented multi-response commands prior to developing the filesystem pipeline, and thus this required a somewhat MacGyver solution to fit in with our current parsing functionality with minimal changes. A more robust command send and response framing architecture for cleaner parsing on both backend and SDPI side will be developed this fall.

Recovery and Persistence after Power Cycles

One software-side goal was to make the system resilient to power cycles (power off then on) and allow it to continue storing data even after a power failure and restart. On the ELVES weather balloon mission, this was unlikely: SDPI would most likely not get power again after power loss. However, power cycles on satellites, which ELFIN intends to use SDPI on, are common, especially to recover from software faults, reset interrupts, or even reset hardware single event upsets (SEU’s).

A naive filesystem design with only the functionalities described previously runs into issues with storing data correctly after a power cycle. Notably, on startup after a power shutoff, each filesystem does not know where their respective filesystem head pointers and next page addresses are. This issue will be addressed in the superblock section.

However, a separate issue is that you still have an incomplete packet at the end of your last written page. You do not know what the remaining bytes of that incomplete packet are because you lost the contents of every in-RAM filesystem buffer on the power cycle. If you append a packet directly onto the start of the next page, searches will no longer work on the filesystem, because incrementing from packets in the previous page to a new one will cause the timestamp check to be looking at the wrong bytes because of those missing bytes causing an offset.

The process to return the filesystem back to a state where more packets can be stored is termed recovery.

A Better Way to do Recovery

Here I will discuss how the “non-destructive recovery” process works. My earlier strategy of recover_fs_state resolved the issue of having an incomplete packet ending the written-to flash by:

- Erasing the last page present in the flash filesystem.

- Loading the contents of that erased page minus the contents of the incomplete packet on that page into in-RAM buffer for each filesystem.

This, while in theory should have worked, turned out to be problematic since I hadn’t implemented superblocks properly at the time and was still running into issues of corruption with filesystem head pointer and next page address. Additionally, this meant losing a page’s worth of data every time I power-cycled the board if I did not store more data.

After shipping a working version of SDPI code with no filesystem recovery for our actual flight (wouldn’t be able to store data post-power cycle but otherwise normal behavior after a filesystem wipe), I realized that SDPI could use the extra space in each page we lost from our addressing scheme. Virtual flash addresses only address the first 4096 bytes of each page, leaving 256 bytes out of the total 4352 bytes unused.

I decided to redesign store_packets to program the QSPI page size instead of just the virtual flash size. Instead of stopping at exactly 4096 bytes each time a page’s worth of data was committed to flash, store_packets now programs a few extra bytes to complete the last packet in the buffer. The next page still continues finishing the previously incomplete packet.

Under this design, the core functionalities of searching and buffer appending have not changed, and we still have the guarantees of a continuous packet filesystem. Buffers were expanded to now be the size of NAND flash pages (4352 bytes) to include the extra bytes that could be past the 4096 byte boundary in order to complete the last packet. Now, store_packets checks if the buffer would be filled past the virtual flash page boundary by the requested data size, adding a packet’s worth of data to the buffer if so.

By doing this, the next page program to flash when the buffer actually is filled past the virtual flash page boundary will program a page that ends on a complete packet somewhere in the 256 bytes spare region.

On startup, we read the last page (next page address minus one full page) and put the remainder of that last packet (the content past the end of the 4096 bytes) into the respective filesystem buffer, to be programmed to flash on the next page write. If SDPI is power cycled here, it ends up in the same state, meaning that no in-flash data is ever lost or corrupted.

Superblocks

One caveat to all of the above post-power cycle operations I have not discussed is the issue of retrieving the correct filesystem head pointer and next page address post power cycles, since they’re typically stored in RAM while the code is running, which is wiped on a board shutdown.

A naive approach to this issue is to, on startup, search from the beginning of each filesystem to the end, page by page, to find the next page address and also to search packet by packet to find the head pointer. Unsurprisingly, this approach was extremely slow and led to startup times ranging from 30 minutes to multiple hours (estimated, we did not actually wait the multiple hours).

A common way to address this and other issues (and is even present on non-flash systems) is to store a superblock. The superblock contains metadata about the filesystem such as the type, status, and indexes of relevant buffers in the filesystem. In the definitions and includes of the filesystem, there is a superblock struct defined that includes information relevant to all filesystems (such as a flag for superblock corruption and an update counter) as well as an array of filesystem structs that include each filesystem’s buffer index, head pointers, next page addresses, and other relevant information.

typedef struct {

fs_packet_t packet_id;

uint32_t packet_size;

uint32_t fs_start_addr; // vflash addr where your filesystem starts

uint32_t fs_head_ptr; // the addr for the next complete packet to be committed to the flash fs

uint32_t fs_next_page_addr; // addr of next page to be committed in the fs

uint32_t buffer_index; // where are we in the buffer (a page's worth of data that isn't persisted to flash yet)

uint16_t fs_num_blocks; // size of filesystem in blocks for this packet

uint16_t fs_wrap_count; // how many times has this fs wrapped

uint8_t fs_last_packet_ts[FS_TIMESTAMP_SIZE]; // ts of last packet that was inserted into this fs

bool fs_erased; // is this fs completely erased? set to false upon first successful store_packets in fs; set to true when erase ran on this fs

bool fs_write_enabled;

bool fs_corrupted;

} fs_t;

typedef struct {

bool superblock_page_corrupted;

bool superblock_region_corrupted;

bool incomplete_shutdown; // set to false during store packet flash write operation, set to true when finished operation and updated sb

uint8_t bad_crc_count; // count of commands received with bad CRC's

uint64_t update_counter; // incremented on each new superblock page

fs_t table[FS_NUM_PACKET_TYPES];

} fs_superblock_t;

The superblock needs to be stored persistently to survive across power cycles, so it is stored in NAND flash. However, every flash operation (store_packets or erase filesystem) updates the superblock and increments the update counter, requiring it to be written to flash. Given the expected data rates, using erase_write to continually write the same block or page is inefficient and causes premature block failure.

Instead, there is a superblock region in flash consisting of two blocks. Each next version of the superblock is written one after the other in consecutive pages, and the whole region wraps by erasing either the first or second block of the region when necessary and continuing to write pages of superblocks.

On power cycle, the filesystem initialization sequence looks through the superblock region for the superblock page with the highest update counter, and loads that superblock into the in-RAM superblock (a virtual flash read followed by a memcpy of the flash superblock into the in-RAM superblock). This means the filesystems are now aware of the previous state in flash prior to a power cycle.

The only time SDPI looks for and loads in a superblock from flash is on startup, and during nominal operations, it only writes superblock pages to flash.

Limitations

The above (minus superblocks and proper recovery) is all I managed to get done before the September 2 deadline. While this was functionally sufficient for our purposes by our launch deadline, I’m aware that there are many optimizations and functionalities that I could have implemented but did not have the time to.

The below features were not implemented by the September 2 deadline and are in varying states of completeness.

- Use of Quad operations for QSPI NAND Flash. From the bit on the NAND flash operations, you can see the 1x IO notation. There is also a 2x, 4x, and Quad version of that command, which are organized in increasing speed. It comes down to how you’re organizing data sent over the four lines. I chose not to implement quad commands this summer to give myself more time to work on the actual filesystem logic.

- Mirroring (use the two other flash chips for bit flip detection) is somewhat computationally expensive to implement, and potentially more effective corruption detection methods are possible.

- Circular filesystems for the packets were not necessary for ELVES, though they need to be implemented in the future for flights of far-longer duration.

- Proper superblocks in flash are implemented but non-destructive recovery after power cycle seems to be failing some tests as of writing this article.

- Non-destructive recovery of the filesystem after power cycles, as mentioned above, still has some issues to be fixed as of writing this article.

- Simpler parsing. There is much to be fixed with regards to extra fields in query and read responses and unmentioned backend architectural issues.

Lessons Learned

This was my first coding/integration-heavy internship so there were many, many lessons learnt that I could not fit into what is already a very long writeup. Here are some of the highlights:

-

Test frequently and often in structured ways, and additionally, write error codes/debugs for states you don’t expect to ever hit. One condition I checked in

store_packetswas if the filesystem head pointer was after the next page address. This should never be true, and I also had trouble reasoning about how it could be made true, but I included the check anyway with the debug message “something is very wrong”. Turns out, we saw this message many times in our UART output 🙂. -

Whiteboard / think about function flow before programming. Many of the features I had to implement this summer had numerous edge cases, often due to hardware limitations that were hard to observe without a cohesive picture of the larger system. This was especially true about the filesystem

store_packetsand updating pointers functionalities, and later on, the superblocks region. Before attempting to write any code, I often drew out the moving parts of the system and observed them functioning in the way I expected them to on a whiteboard to see potential problems and unexpected behavior. - Be intentional with what you don’t include in your API. In the same vein as the lessons from the legendary blog Joel on Software, minimal and simple is best. I aimed to abstract as much of the hardware-specific NAND flash details as I could and hide them under the virtual flash driver to expose as minimal a function set as I could. These choices helped me later on when writing filesystem functions, by restricting the possible functions I could use, forcing me to design smarter and unwittingly optimizing for fewer NAND flash operations.

-

Commit frequently and make an honest effort to use commits as “versions”. While I had a relatively extensive theoretical knowledge of git from my school-year classes, this summer allowed me to put these skills into practice. Looking back on my previous commits, I found that there were many extraneous commits that made cosmetic changes (variable renaming for standardization) that could be grouped together in one commit. The opposite problem was also present: I saw different functional changes that were coalesced into one commit. Late in the internship, I started using

git commit --amendto append small changes to previous commits to make the git history cleaner, and to commit more frequently for debugging versioning. Additionally, I started to use git tagging for identifying our testing and flight-ready versions of code. These changes greatly benefited my debugging process especially as the bugs I ran into became more complex as more systems were integrated together. - Fewer assumptions can be made on embedded systems. Many issues I ran into while designing the filesystem had to do with memory handling and allocation. For example, I ran into strange corruption that I discovered was stack clobbering. It turns out that I statically allocated buffers of 4,200 bytes each at runtime on a microcontroller with a stack of only 8,192 bytes. While this issue was obvious in hindsight, it was not obvious to me as someone who was used to not having to think about stack sizes smaller than a MB on desktop or laptop computers.

- Integration is difficult. Maybe the biggest lesson in designing such interconnected systems was that integration tests will reveal many issues (timing, parsing, data handling) that are difficult to anticipate ahead of time. The takeaway here was to allocate significant amounts of time for integration testing and consider cutting down on your feature set in order to have the time to do complete integration tests.

Inspiration / References

Thanks to the entire ELFIN team for making this a super enjoyable summer! Everyone was really courteous, hardworking, and incredibly knowledgeable, and I couldn’t have asked for a better group of people to work with.

Some articles and presentations that I took inspiration from when writing this one:

- “Engineering for Slow Internet - How to minimize user frustration in Antarctica.” was a deeply interesting writeup that inspired me while I was working on this project over the summer.

- Jasmine Tang’s “What I did for GSoc 2024” was a to-the-point, yet deeply technical view of a self-motivated summer internship-like experience, the style of which I hoped to emulate in this blog post.

- “Hacking yourself a Satellite” is a classic, but still legendary to me. It’s super cool to me that the old ELFIN team at UCLA did something similar (code injection) in order to upgrade the capabilities of the twin ELFIN satellites during their 4-year mission.

This article was kind of a word barf of everything technical that happened over my summer. Thanks for making it this far! Hope you found this read enjoyable.